Stepping off the plane into the Middle East was like stepping in front of a hairdryer. Hot, dry wind blew into my face, which I grew to appreciate because it was better than no wind. In July 2021 I started my first overseas deployment. I had just completed my emergency medicine residency and had volunteered for a deployment with the U.S. Army National Guard.

I was the brigade surgeon with the engineering unit I’d been assigned to. My job was to provide medical recommendations to the commander. I had no idea what type of useful medical recommendations I’d be able make for a unit at a stable base, however at the first meeting I attended with the command staff, there was talk about evacuating American citizens and Afghanis who assisted America during the war in Afghanistan.

The preparations were in two main sections: housing and support. There weren’t enough empty buildings for the expected soldiers and civilians at our location at Camp Buehring, so the engineer brigade’s mission was to prepare unoccupied land for temporary tents that could be used for potential Afghan refugees but could also be utilized for other purposes. If the Afghan refugees did come to our location, we would need to support them with food, sanitation, water, and medical care.

For over a month we worked and planned. Though the occupants of the land being prepared were undefined and there was a possibility the area wouldn’t be utilized for the evacuation of Afghanistan, we were told to have the site ready for tens of thousands of individuals. My two main roles during the project were to monitor the health of the soldiers running heavy machinery in the desert heat and provide the brigade commander with health and welfare consultation concerning the design and functions of the camp.

I created an education for the soldiers working in the desert heat and monitored their welfare to prevent heat casualties. I also requested that an air-conditioned tent be placed near the work area, so the soldiers could rest in cool air when they took breaks. There were no heat casualties despite temperatures over 120°F in the heavy construction machines.

For evacuees, we planned universal COVID-19 screening and initial medical treatments. We didn’t have enough medical staff when split between two 12-hour shifts to manage all the COVID screening, so we trained volunteer soldiers of any background to help.

.jpg)

Physician and medic evaluating a patient at the in-processing center.

We organized two provider rooms for treatment and screening. The design engineer and I sat together and planned bed organization within the tents to maximize space between individuals as well as the number of beds. We wanted every head to be 6 feet from every other head while sleeping to reduce the spread of respiratory diseases like COVID. We planned an upwind location for isolation tents for evacuees who tested positive for COVID or other contagious diseases.

Following the fall of Kabul on August 15, 2021, the first Afghani special immigrant visa (SIV) applicants were transported to Qatar. On August 22, Kuwait authorized the use of our base as a temporary receiving facility for SIV applicants. Within 18 hours, the first planeload arrived.

.jpg)

The first bus of Afghani evacuees arrives at the in-processing center. Buses from the airport were courtesy of Kuwait’s National Guard.

The first flight carried 78 adult males, 78 adult females, and 297 children. Our military medical colleagues in Qatar had reported a significant number of unaccompanied minors. Thankfully, less than a handful of unaccompanied children came through our country. With the large number of children on this flight, our behavioral health provider, whose civilian job is a social worker in public schools, volunteered to provide structured play for the children and assistance with emotional needs. A picture of her blowing bubbles for the children trended on social media.

Everyone who arrived at our facility needed to be in-processed, which consisted of COVID-19 testing, filling out a health questionnaire, visiting a provider if they had any medical concerns, picture taking for identification purposes, and tent assignments. Our small medical unit with the engineering brigade consisted of a brigade surgeon (myself), a physician assistant, and six medics. We were augmented by an additional physician or physician assistant and a couple of medics from another unit. During the operation, we were present and available for the thousands of people who walked through the doors. We relied on translators arriving from Afghanistan with their families to assist us.

.jpg)

Forms in Pashto and English that helped identify chronic illnesses requiring urgent treatment such as diabetes and hypertension.

I took the opportunity to talk to the translators to learn a little about them. One was a physician who went to school in Europe. “I went back to my country after my training because I love Afghanistan, but with the Taliban taking over, I had to leave for the sake of my wife and daughter,” he said. I asked if he was going to work as a physician in America, but he wasn’t sure.

Since there were only two providers in our unit, I worked the day shift, and the physician assistant worked at night. The most common immediate health problem we saw was heat illness.

.jpg)

Joint forces treatment team preparing for patients. Army and Air Force combined equipment, medications, and personnel to make this mission a success.

We saw symptoms that included, headaches, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and elevated temperatures. One woman with epilepsy went into status epilepticus due to the physical stress and required evacuation to a larger clinic on the base for treatment. Ondansetron ODT fixed almost all the nausea and vomiting, which allowed us to administer oral rehydration salts. Those with elevated temperatures and no other symptoms were given oral rehydration fluids and also placed near an air conditioning vent to cool down.

.jpg)

One of the treatment areas at the in-processing tent. On the wall are the large air conditioning vent openings that allowed us to cool patients rapidly.

Upon recheck, their temperatures had normalized. A few required IV rehydration due to intractable vomiting, but after 1L of IV fluid, their nausea resolved, and they were able to drink again. IV fluids were limited, so whenever possible we used oral rehydration.

A few of the children had strep throat diagnosed clinically with tonsillar exudates and sandpaper rash. For obvious reasons, the military doesn’t stock pediatric medications on deployments.

.jpg)

Limited medications were available. This improved slightly after a few days thanks to the U.S. embassy.

We diluted adult medications with Pedialyte (carried in our store on the base to treat dehydration) to provide the needed antibiotics. We didn’t have a scale for weight-based doses. Instead, we used a phone application called PediStat that takes input of one of four variables including age, then lists medication doses based on the Broselow scale. Within 24 to 36 hours, the local government and the U.S. Embassy provided essential over the counter pediatric medications. The Red Cross distributed shoes, clothing, bottles, and other goods.

A physician from another unit who volunteered to work with us had a point-of-care ultrasound that allowed us to evaluate pregnant women. Their expected gestation was often one month off or more from what we saw on exam and ultrasound. We saw no significant pregnancy complications.

The medical tent in the camp where the majority of the SIV applicants were housed started as an empty tent identical to the housing. Temporary patient rooms were created with 550 paracord and sterile blue drapes. The engineers erected solid walls the next day, but the 550 cord and blue drapes remained as curtained entrances. It was an effective and efficient use of materials.

After we had received all the evacuees destined for our location, the in-processing center closed and my unit returned to our regular duties, while a hospital company continued to take care of the health needs of the evacuees in the camp. The brigade physician assistant and I volunteered for several shifts with their staff. During this time, I had the opportunity to talk to another translator. This one had worked with American military units and had owned a successful restaurant in Kabul where he played rock music on his guitar. I asked about his plans in America. “I have a friend in New York City who wants me to open a restaurant with him.” He was very excited and talked about both his future and his past experiences as a business owner.

.jpg)

The sun sets on the SIV living area hours before the last few families leave. The medical tent was the 5th tent in.

By September 6th, all SIV applicants had left Camp Buehring for other sites in Europe or military bases in the US. None of us expected this experience when we left for deployment. The mission went well due to the planning and consistent effort from everyone involved. This operation demanded flexibility, resourcefulness, and ingenuity.

Some children arrived without shoes, so an airman made sandals.

I saw military personnel do everything from making sandals, to treating pregnant women (not a common soldier task), to making balloon toys from medical gloves. It was a once in a lifetime opportunity to make a difference. As one of the mechanics-turned-COVID testers said, “This feels like what I joined the Army to do.”

Two teenage sisters each drew a flag of the two countries they love and unified them. Symbolic of the attitudes of many I spoke to.

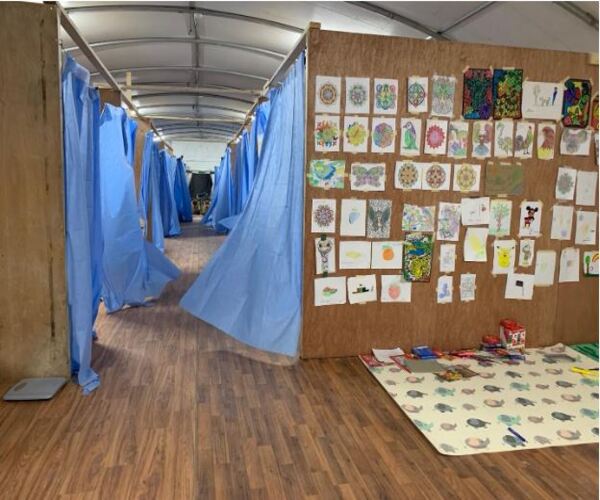

The tent clinic in the SIV camp. The medics created a coloring and play area for kids and posted their drawings on the wall. Some kids hung out for hours to play and relax.

Videos:

DOD video of our site in Kuwait. I’m in the background at 0:40.

Our site from CENTCOM